You can already play... You move first. Good luck!

If you are using a phone or tablet, hold it horizontally.

|

Introduction

Chess is a recreational and competitive strategy game for two players. Today, chess is one of the world's most popular sports, played by an estimated 605 million people worldwide. Chess is also advocated as a way of enhancing mental prowess. The game is played on a square chequered chessboard. At the start, each player ("White" and "Black") controls sixteen pieces: one king, one queen, two rooks, two knights, two bishops, and eight pawns. The object of the game is to checkmate the opponent's king, whereby the king is under immediate attack (in "check") and there is no way to remove it from attack on the next move. Theoreticians have developed extensive chess strategies and tactics since the game's inception.

^ TOPThe chess board

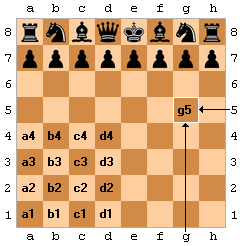

Chess is played on a square board of eight rows (called ranks and denoted with numbers 1 to 8) and eight columns (called files and denoted with letters a to h) of squares. The colors of the sixty-four squares alternate and are referred to as "light squares" and "dark squares". The chessboard is placed with the light squares at the players' right, and the pieces are set out as shown in the image, with each queen on its own color.

The position of the pieces at the start of a game of chess

^ TOP

Rules

The pieces are divided, by convention, into White and Black sets. Each player, referred to by the color of his pieces, begins the game with sixteen pieces: these comprise one king, one queen, two rooks, two bishops, two knights and eight pawns. White moves first. The colors are chosen either by a friendly agreement, by a game of chance or by a tournament director. The players alternate moving one piece at a time (with the exception of castling, when two pieces are moved at the same time). Pieces are moved to either an unoccupied square, or one occupied by an opponent's piece, capturing it and removing it from play. With one exception (en passant), all pieces capture opponent's pieces by moving to the square that the opponent's piece occupies.

When a king is under direct attack by one (or possibly two) of the opponent's pieces, the player is said to be in check. When in check, only moves that remove the king from attack are permitted. The player must not make any move that would place his king in check. The object of the game is to checkmate the opponent; this occurs when the opponent's king is in check, and there are no moves that remove the king from attack.

Each chess piece has its own style of moving.

- The king can move only one square horizontally, vertically, or diagonally. Once in every game, each king is allowed to make a special move, known as castling. Castling consists of moving the king two squares towards a rook, then placing the rook (immediately) on the far side of the king. Castling is only permissible if all of the following conditions hold:

- The player must never have moved both the king and the rook involved in castling;

- There must be no pieces between the king and the rook;

- The king may not currently be in check, nor may the king pass through squares that are under attack by enemy pieces. As with any move, castling is illegal if it would place the king in check.

- The king and the rook must be on the same rank (to exclude castling with a promoted pawn). - The rook moves any number of vacant squares vertically or horizontally (it is also involved in the king's special move of castling);

- The bishop moves any number of vacant squares in any direction diagonally. Note that a bishop never changes square color, therefore players speak about "light-squared" or "dark-squared" bishops;

- The queen can move any number of vacant squares diagonally, horizontally, or vertically;

- The knight can jump over occupied squares and moves two spaces horizontally and one space vertically or vice versa, making an "L" shape. A knight in the middle of the board has eight squares to which it can move. Note that every time a knight moves, it changes square color.

- Pawns have the most complex rules of movement:

- A pawn can move forward one square, if that square is unoccupied. If it has not yet moved, the pawn has the option of moving two squares forward, if both squares in front of the pawn are unoccupied. A pawn cannot move backward.

- When such an initial two square advance is made that puts that pawn horizontally adjacent to an opponent's pawn, the opponent's pawn can capture that pawn "en passant" as if it moved forward only one square rather than two, but only on the immediately subsequent move.

- Pawns are the only pieces that capture differently than they move. They can capture an enemy piece on either of the two spaces adjacent to the space in front of them (i.e., the two squares diagonally in front of them), but cannot move to these spaces if they are vacant.

- If a pawn advances all the way to its eighth rank, it is then promoted (converted) to a queen, rook, bishop, or knight of the same color. In practice, the pawn is almost always promoted to a queen.

Chess games do not have to end in checkmate - either player may resign if the situation looks hopeless. Games also may end in a draw (tie). A draw can occur in several situations, including draw by agreement, stalemate, threefold repetition of a position, the fifty move rule, or a draw by impossibility of checkmate (usually because of insufficient material to checkmate). ^ TOP

Notation for recording moves

Chess games and positions are recorded using a chess notation, most often the algebraic chess notation. The abbreviated (or short) algebraic notation generally records moves in the format abbreviation of the piece moved - file where it moved - rank where it moved, e.g. Qg5 means "Queen moved to file g and rank 5 (that is, to the field g5). If there are two pieces of the same type, which can move to the same field, one more letter or number is added to indicate the file or rank from which the piece moved, e.g. Ngf3 means "Knight from the file g moved to the field f3". Letter P indicating a pawn is usually dropped, so that e4 means "Pawn moved to the field e4".

Algebraic chess notation

If the piece captures, "x" is inserted behind the abbreviation of the piece, e.g. Bxf3 means "Bishop captured on f3". When a pawn makes a capture, the file from which the pawn departed is used in place of a piece initial. For example, exd5 (pawn on the e-file captures the piece on d5).

If a pawn moves to its last rank, achieving promotion, the piece chosen is indicated after the move, for example e1Q. Castling is indicated by the special notations 0-0 for kingside castling and 0-0-0 for queenside. A move which places the opponent's king in check usually has the notation "+" added. Checkmate can be indicated "#" (some use "++"). At the end of the game, "1-0" means "White won", "0-1" means "Black won" and "˝-˝" indicates draw.

Chess moves can be commented by punctuation. For example ! indicates a good move, !! an excellent move, ? a mistake, ?? a blunder, !? an interesting move that may not be best or ?! a dubious move, but not easily refuted.

For example, one variant of a simple trap known as the Scholar's mate, animated in the picture below, can be recorded:

1. e4 e5

2. Qh5?! Nc6

3. Bc4 Nf6??

4. Qxf7# 1-0

The "Scholar's mate"

Strategy and tactics

Chess strategy consists of setting and achieving long-term goals during the game - for example, where to place different pieces - while tactics concentrate on immediate maneuvers. These two sides of chess thinking cannot be completely separated, because strategic goals are mostly achieved by the means of tactics, while the tactical opportunities are based on the previous sound strategy of play.

Because of different strategic and tactical patterns, a game of chess is usually divided into three distinct phases: Opening, usually the first 10 to 25 moves, when players develop their armies and set up the stage for the coming battle; middlegame, the developed phase of the game; and endgame, when most of pieces are gone and kings start to take an active part in the struggle.

Fundamentals of strategy

Chess strategy is concerned with evaluation of chess positions and with setting up goals and long-term plans for the future play. During the evaluation, players must take into account the value of pieces on board, pawn structure, king safety, space, and control of key squares and groups of squares (for example, diagonals, open-files, and dark or light squares).

The most basic task is to count the total value of pieces of both sides. The point values used for this purpose are based on experience; usually pawns are considered worth one point, knights and bishops about three points each, rooks about five points (the value difference between a rook and a bishop being known as "the exchange"), and queens about nine points. The fighting value of the king in the endgame is equivalent to about four points. These basic values are then modified by other factors like position of the piece (for example, advanced pawns are usually more valuable than those on initial positions), coordination between pieces (for example, a pair of bishops usually coordinates better than the pair bishop + knight), or type of position (knights are generally better in closed positions with many pawns while bishops are more powerful in open positions).

Another important factor in the evaluation of chess positions is the pawn structure (sometimes known as the pawn skeleton), or the configuration of pawns on the chessboard. Pawns being the least mobile of the chess pieces, the pawn structure is relatively static, and largely determines the strategic nature of the position. Weaknesses in the pawn structure, such as isolated, doubled or backward pawns and holes, once created, are usually permanent. Care must therefore be taken to avoid them unless they are compensated by another valuable asset (for example, by the possibility to develop an attack).

Fundamentals of tactics

In chess, tactics in general concentrate on short-term actions - so short-term that they can be calculated in advance by a human player or by a computer. The possible depth of calculation depends on the player's ability or speed of the processor. In quiet positions with many possibilities on both sides, a deep calculation is not possible, while in "tactical" positions with a limited number of forced variants, it is possible to calculate very long sequences of moves.

Simple one-move or two-move tactical actions - threats, exchanges of material, double attacks etc. - can be combined into more complicated variants, tactical maneuvers, often forced from one side or from both. Theoreticians described many elementary tactical methods and typical maneuvers, for example pins, forks, skewers, discovered attacks (especially discovered checks), zwischenzugs, deflections, decoys, sacrifices, underminings, overloadings and interferences.

A forced variant which is connected with a sacrifice and usually results in a tangible gain is named a combination. Brilliant combinations - such as those in the Immortal game - are described as beautiful and are admired by chess lovers. Finding a combination is also a common type of chess puzzle aimed at development of players' skills.

Opening

A chess opening is the group of initial moves of a game (the "opening moves"). Recognized sequences of opening moves are referred to as openings and have been given names such as the Ruy Lopez or Sicilian Defense. They are catalogued in reference works such as the 'Encyclopedia of Chess Openings'.

There are dozens of different openings, varying widely in character from quiet positional play (e.g. the Réti Opening) to very aggressive (e.g. the Latvian Gambit). In some opening lines, the exact sequence considered best for both sides has been worked out to 30-35 moves or more. Professional players spend years studying openings, and continue doing so throughout their careers, as opening theory continues to evolve. Uncovering one or two novelties in opening theory can be key to success in a high level match or tournament.

The fundamental strategic aims of most openings are similar:

- Development: To place (develop) the pieces (particularly bishops and knights) on useful squares where they will have an impact on the game.

- Control of the center: Control of the central squares allows pieces to be moved to any part of the board relatively easily, and can also have a cramping effect on the opponent.

- King safety: It is often enhanced by castling.

- Pawn structure: Players strive to avoid the creation of pawn weaknesses such as isolated, doubled or backward pawns, and pawn islands.

Middlegame

The middlegame is the part of the game when most pieces have been developed. Because the opening theory has ended, players have to assess the position, to form plans based on the features of the positions, and at the same time to take into account the tactical possibilities in the position.

Typical plans or strategical themes - for example the minority attack, that is the attack of queenside pawns against an opponent who has more pawns on the queenside - are often appropriate just for some pawn structures, resulting from a specific group of openings. The study of openings should therefore be connected with the preparation of plans typical for resulting middlegames.

Middlegame is also the phase in which most combinations occur. Middlegame combinations are often connected with the attack against the opponent's king; some typical patterns have their own names, for example the Boden's Mate or the Lasker-Bauer combination.

Another important strategical question in the middlegame is whether and how to reduce material and transform into an endgame. For example, minor material advantages can generally be transformed into victory only in an endgame, and therefore the stronger side must choose an appropriate way to achieve an ending. Not every reduction of material is good for this purpose; for example, if one side keeps a light-squared bishop and the opponent has a dark-squared one, the transformation into a bishops and pawns ending is usually advantageous for the weaker side only, because an endgame with bishops on opposite colors is likely to be a draw, even with an advantage of one or two pawns.

Endgame

The endgame (or end game or ending) is the stage of the game when there are few pieces left on the board. There are three main strategic differences between earlier stages of the game and endgame:

- During the endgame, pawns become more important; endgames often revolve around attempting to promote a pawn by advancing it to the eighth rank.

- The king, which has to be protected in the middlegame owing to the threat of checkmate, becomes a strong piece in the endgame and it is often advisable to bring it to the center of the board where it can protect its own pawns and attack the pawns of opposite color.

- Zugzwang, a disadvantage because the player has to make a move, is often a factor in endgames and rarely in other stages of the game.